Ten thoughts on sports betting

It's a bad sign when something starts to resemble a slot machine

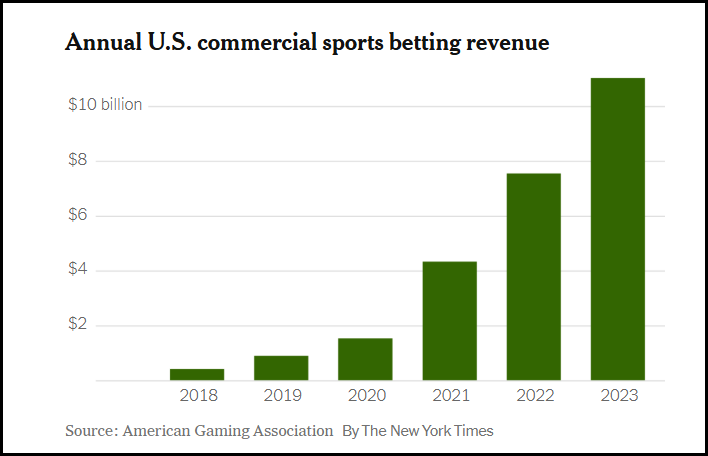

Sports betting is all over the news right now. The recent NBA gambling scandal involving allegations of player stats-fixing has reignited a public policy debate over the explosion of legal gambling in the United States in the last 40 years, and in particular the massive rise of sports betting since 2018, when the Supreme Court struck down the federal ban. Public opinion has begun to turn against the expansion of legal gambling, which an increasing number of Americans see as bad for society.

Gambling—legal or illegal—naturally has both costs and benefits. The main benefit is that a heck of a lot of people really enjoy it as a form of entertainment; go anywhere where people are gathered in leisure activity, and you will quickly observe recreational gambling. It undoubtedly adds to the happiness of many people. It also raises a heck of a lot of tax money for states.

The biggest problems mostly stem from addiction, and they are far from trivial. In many cases, gambling addictions are just as destructive, or more destructive, than alcohol or drug addictions. Problem gamblers often have difficulty holding a job, and may face financial ruin. They often become socially isolated and have increased rates of suicide. And it can often be hidden from friends and family much longer than other addictions that have more obvious physical manifestations.

There are also negative externalities for society. Problem gambling is associated with domestic violence and higher rates of divorce. It highly correlates with criminal activity. And there’s a reason many people are NIMBYs about the building of new casinos in their neighborhood; the generalized economic returns do not outweigh the localized problems that seem to inherently come with casinos.

It’s not at all surprising that many Americans have moral concerns about gambling, and reservations about its legal expansion.

Here are ten thoughts on sports betting, how it fits into the world of gambling, and how it is changing in the modern age.

#1. Gambling is an umbrella word for an incredibly wide variety of activities.

It’s actually pretty weird that we loosely group all the following together:

four friends betting $25 each on their Saturday afternoon golf match;

playing blackjack at a casino for $25 a hand;

putting $25 into an online betting market on the outcome of the Virginia gubernatorial election;

buying a $25 lottery scratch-off ticket;

playing poker for $25 at your kitchen table with your family;

betting your buddy $25 on the outcome of the Army-Navy football game;

entering a $25 Scrabble tournament that has cash prizes;

simultaneously playing five $5 online poker tournaments; and

dropping $25 into a Vegas slot machine.

Each of these things involves gambling $25. But they aren’t even remotely the same activities. Some of them—especially the Scrabble tournament—might not even strike you as gambling at all.

#2. The individual and societal impacts of gambling vary across these types. The moral concerns of cash prize Scrabble tournaments are just completely different than those of state lotteries, and the socially optimal level of weekend golf betting among friends is almost completely orthogonal to that of casino blackjack. Naturally, such distinct moral, social, and economic dimensions suggest varying public policies we might consider for each of them.

Here’s a back-of-then-envelope five-point empirical framework for thinking about the relative individual and social value of the various types of gambling, with corresponding points:

Is it skill-based or random? Betting on your own physical or mental skill is, on average, less potentially destructive than betting on random outcomes, because it partially separates the gambling from the activity. If the activity can be enjoyed without betting on it, that’s usually a good sign; as the USGA notes in its guidelines for gambling on golf, it’s not at all objectionable when it’s not the primary purpose of the golfing. On the other hand, nobody plays roulette without betting on it. [For the empirical framework, assign one point for skill-based gambling, zero points for gambling on random outcomes.]

Is it against other competitors, or is there a house? Betting against other competitors is a neutral playing field. Betting against a house creates a third-party commercial incentive to encourage more gambling, at a faster pace, for higher stakes. In effect, the house has a market incentive to create and facilitate problem gambling. [One point for betting against other competitors, zero for betting against the House.]

Is it negative expected value? It’s certainly possible for winning gamblers to be problem gamblers, but much of the individual problems and negative externalities of gambling come from the lost money, plain and simple. And if the gambling has a negative expected value over the long-run, it’s just going to create way more losing. [If all the money that goes into the bet comes out to one or more winners, one point. If the activity entails a rake, vig, or hold that goes to a house, either half a point or zero points, depending on if it’s small or large.]

Is it a social or solitary activity? Problem gambling is highly correlated with loneliness, and gambling alone inherently misses out on all of the positive externalities of human interaction. On balance, if you need to call up some friends and meet up with them to engage in a gambling activity, that’s going to be net significantly less destructive than any solo gambling endeavor, all else equal. [If the gambling activity typically occurs in a group of two or more humans, 1/2 point. If they are people you know, another 1/2 point. If you generally do it alone, zero points.]

How often do you make an individual bet? The speed of gambling matters. It’s harder, on balance, to chase losses and compulsively gamble more than necessarily should if you don’t have actual opportunities to wager. So if a wager’s outcome doesn’t settle for 3 hours, that’s a lot less potentially dangerous than if the outcome settles in 3 minutes. (Related to this, but not exactly the same, is the friction involved in making a wager. How much effort is required to actually bet? But more on that later.) [If there are 30 or more minutes between each possible wager (that’s an essentially random number I just made up), one point. If there are less, zero points.]

Notice that I have not included the monetary size of the wager as a dimension. That’s largely because it’s independent of the type of gambling; you can bet a tiny amount of a large amount on essentially any type of wager. And that is not to say it is unimportant—betting beyond your means is perhaps the surest sign of problem gambling—but instead a recognition that it’s a universal potentially problematic dimension of all gambling endeavors.

#3. Here are the scores of some common gambling activities under this framework. Maximum score would be five—indicating a gambling activity that is skill-based, against other competitors, not negative EV, a social activity, and with long periods between bets. A zero would indicate betting on random outcomes, against the house, with negative expectation, alone, in rapid succession. Again, this is a back-of-the-envelope framework and also reflects some judgement calls I made (e.g. do you know the people at your local poker room? Are you alone at a blackjack table? Is blackjack a game of skill? Is it really skilled to bet on horse races for most people? etc.)

Family poker tournament: 5

Betting with friends on a golf match: 5

Public Scrabble tournament: 4.5

Betting your buddy you can make a 3-point shot: 4

Home game poker for cash: 4

Public card room poker tournament: 3.5

Betting on a horse race you are at: 3

Public card-room poker for cash: 3

Online poker for cash: 2

Casino table games: 1-2, depending on game/conditions1

Mega Millions lottery ticket: 1

Lottery scratch-off ticket: 0

Online roulette: 0

Casino slot machine: 0

I think this list roughly validates the back-of-the-envelope framework, in the sense that eyeballing this roughly corresponds with how I think most knowledgeable gamblers would rank the destructiveness of the various activities.

#4. Slot machines are very, very bad. They got a zero on my framework, but that probably understates how awful they are. If you want the full and devastating details, just read Addiction by Design. Everything about the slot machine reflects more than 100 years of research and testing on how to best create and maintain gambling addicts.

Even at low stakes—like “$1” machines—you can gamble a massive amount of money very quickly, with almost zero “friction,” which is anything and everything that puts time or difficulty between you and your next wager. The negative EV and the variance of the machines are set precisely to maximize long-term monetary losses. They are installed in long maze-like banks specifically to give problem gamblers the feeling of being alone and hidden, where they can get in the “machine zone” trance and ride a dopamine drip until the money is gone.

Even worse, slot machines are huge moneymakers for casinos. It’s easy to think of a blackjack table as the symbol of a Vegas casino, but those days are long gone. Unlike an image you might have in your head from the 1960s, the vast majority of the space at any casino is now allocated to slots, not table games. They have a bigger house advantage. They have much lower labor costs. And they allow problem gamblers a much more conducive environment to enable their addiction.

I think I have only played a slot machine twice in my life. The most recent time was when my family was on vacation in Vegas, and the MGM-branded credit card I have (primarily to get free parking at poker rooms) had also generated me about $100 in free slot play. I was shocked at how quickly I blew through the $100—it literally took me like 3 minutes.

#5. Thesis: the more a gambling-activity resembles a slot machine, the more we should worry about it. In some sense, every game you play against the house at a casino is just a dressed-up slot-machine, a negative EV gamble, but less efficient because of the friction required to attract people to play it who don’t enjoy using an actual slot machine. That’s what I see, anyway, anytime I am walking through a casino to get to the poker room.

And so the blackjack table has a dealer because people like the human dealing real physical cards and you have to deal the real physical cards out and so you can only actually make a wager about once a minute instead of once every 5 seconds and the house edge is much, much lower on those bets anyway. Ditto with the craps table, except there the house also has to put up with the very social nature of the endeavor, with people spending time getting girls to blow on the dice and boisterously celebrating together when they win. All of this makes blackjack and craps—the most prominent of the social table games—very unlike slot machines.

But both blackjack and craps can easily be made to more closely resemble a slot machine: you can remove the humans. One way to do this is to literally convert the casino table games into table-game slot machines; lots of Vegas casinos now have sections where you can play blackjack or roulette or craps in an automated format, without a real deal or other gamblers sitting next to you. Less friction, faster gambling.

Of course, the other way to turn all of this into a slot machine is the internet, which is the ultimate friction-reducer. Not only does it make a hand of blackjack go faster, it removes all of the friction of even getting to a casino.

People are right to be very worried about internet gambling. It turns a lot of types of gambling more or less into slot machines.

#6. Sports betting is increasingly looking like a slot machine. There is a version of sports betting that’s actually a really great and positive form of gambling. It’s the one done by a massive number of Americans every week in the fall: office NFL pick’em pools. Like the one my mother-in-law did for years in the faculty lounge at the high school she taught at. It scores really well on my framework—somewhere between a 4 and 5 depending on if you think it’s skilled (more on this in a moment). Ditto with March Madness college basketball brackets. And ditto with betting your buddy $20 on the outcome of the Giants-Redskins game, because you each like one of the teams.

But modern sports-betting is trending in exactly the opposite direction. There has always been a pretty big illegal market for serious sports betting against a house, that’s not new. But the legalized version has at least three new features. The first, of course, is that it’s legal. Illegal bookmakers certainly have/had profit motives in the past, but they didn’t have the ability to advertise endlessly during NFL broadcasts. Or directly sign partnerships with the sports leagues themselves.

Second, again obviously, is the internet. Putting the sportsbook in everyone’s pocket dramatically reduces the friction to place a bet, and also makes it easier to make a negative EV bet against a house than to make a neutral EV bet against your friends. I don’t think it was particularly hard to find a bookie in 1994, but it still took some effort, some risk, and some trust. Now the human interaction is completely gone. Just you and the machine.

Third, and related, is that the internet unlocks the full potential of continuous betting. Once upon a time, a sports bet was a slow wager. The fastest wager you might be able to make, pre-internet, was something like a bet on the first quarter of an NFL game. Now you can literally find bets on the outcome of the next play. The lines on games are constantly updated, minute-by-minute, meaning there are dozens of betting opportunities, constantly, during an NFL game.

#7. Related, the expected value of sports bets are getting worse. The house edge on a traditional sports bet (like a bet against the spread on an NFL game) is about 4.5%. But the modern internet sportsbooks have discovered a new twist on an old gambling reality: bettors love longshots that have a chance to win a lot of money on a small wager.

This is a well-known economic phenomenon in gambling called favorite-longshot bias. I’ve written a full blog post about it in the past, but it boils down to this: gamblers prefer to bet on a longshot with a big potential payout over a favorite with a small potential payout, even if the longshot has a much worse EV. This has been empirically proven again and again in horse-racing, but it also has an obvious application to the sports-betting market: people love single-game parlays, which are linked bets that multiple things will happen in a game. Like “the Giants will win, the total points scored will go over 40, and Jaxson Dart will throw 3 or more touchdowns.”

The rub is that—as with all longshot bets—sportsbooks can get away with charging a higher house edge on single-game parlays. This is actually true across all forms of gambling; there’s a strong correlation between the odds of the bet and the house edge in offering it; even money bets (like blackjack and craps) tend to have small house edges, but ultra longshot bets (like state lotteries and huge jackpot slot machines) tend have huge house edges.

Why is that? A few reasons. First, losing bettors don’t worry about the edge. When you buy a lottery ticket, you just pay your $2 and 99.9999% of the time you don’t hit the jackpot. And so you never see that the prize has a horrible house edge built into it, and the EV is massively negative. Second, when you do hit a longshot, the prize is large relative to the wager, so the house edge is less apparent. People would go crazy if they won a $10 hand of blackjack and were only given $7. But hit a $2 lottery scratch ticket for $1000, and no one even thinks about how the odds were actually 4000-1 or whatever.

And, of course, anytime bettors love something and it has a higher house edge, you are going to get it in spades from the house. And so every DraftKings ad now features single-game parlays, which have a typical house edge of 20-30%, which is like five to seven times larger than a traditional sports bet. And parlay bets are now accounting for a huge fraction of the revenue and profits of the sportsbooks. And the internet makes them easier to build than ever. And there’s no friction left.

And sports betting is looking more and more like a slot machine.

#8. Sports betting is theoretically beatable, but not really. One allure of sports betting has always been that, in principle, it’s a skilled bet. That means it is sometimes grouped with poker as the two forms of gambling at a casino that aren’t inherently negative EV games. And indeed, there are professional sports bettors who make a living doing it. Some of them are fabulously wealthy.

But it’s mostly an illusion. For 99% of people, sports betting is just random betting. To win at casino poker in the long-run, you need to have an aggregate edge on the 8 other people at the table, and that edge has to be big enough to overcome the house rake from the game. That’s a lot harder than beating your home game, but it’s totally doable. Lots of people do it, and with a modest amount of study, it’s within the grasp of many people, at least at the lower stakes games that are populated by recreational players there to have a good time.

To win at sports betting, you need to have an edge on lines that are set by the aggregate knowledge and betting patterns of the best bettors and handicappers in the world, and that edge needs to be big enough to overcome the house rake. The people who can do it are extensively modeling sports outcomes using high quality data and proprietary models, and then racing to get money down before the lines change. And that’s to get a small 2-5% edge. The average person has no chance of coming close to that. Ever.

If you could have the lines set by the 8 other people at your poker table before the actual lines come out, then you might have a chance. Against the NFL lines on Sunday afternoon after the best bettors in the world have already gotten to them? You are drawing dead.

#9. The sportsbook operators aren’t just neutral actors facilitating wagers. Sometimes you will see sportsbooks presented—again, alongside poker rooms—as neutral operators, who don’t care about the outcome of the gambling because they are just there to facilitate it and take their cut. And indeed, that is what’s happening in a poker room. The house provides the dealers and the tables and the security, but they don’t have an interest in who wins or loses. You aren’t betting against them. They just take their fees and you just have to beat the other players.

Sportsbooks aren’t really like that. Yes, they offer both sides of the same bet (and their edge guarantees a profit if they get equal amounts of money wagered on each side), but they can’t know that their lines are correct and they can’t guarantee that they get equal action. One sharp sports bettor who has a superior model than them could theoretically come in and make a massive +EV wager, costing them a lot of money.

For this reason, the sportsbooks don’t like sharp gamblers. And as soon as they find out you have any proclivity for it—either because you are a consistent winner or simply because you routinely grab best on lines that subsequently settle the other direction (known as CLV in the parlance) or even if you just routinely place bets right as the lines come out—they will attempt to limit your gambling, usually by putting a cap on how much you can bet on any game.

They want the losing bettors to bet as much as possible, but anyone who might be a winner is quickly neutralized.

#10. None of this makes it obvious how to regulate sports betting. Would we be better off without legal sports betting? It’s hard to say. The internet isn’t going anywhere, and illegal sports betting with off-shore sportsbooks will always be an option for gamblers. A ban would obviously increase the friction of betting—you wouldn’t be able to fund an account with Paypal—and it would also cut off the advertising and the league partnerships that are drenching every NFL game with betting-related inducements. But how much gambling would it actually reduce? That’s unknown.

Proponents of legal sports betting also point out that DraftKings and FanDuel are in the best position to identify irregularities in betting patterns that might indicate nefarious gambling-related match-fixing among players. That, of course, creates a chicken-and-egg issue, since such match-fixing almost certainly has become a larger temptation in the age of ubiquitous slot-machine-like legal sports betting.

If I had to guess, I think the trajectory of public opinion is such that some form of increased regulation is coming, perhaps in limitations on types of sports bets or the structures of the single-game parlays or some artificial friction in the internet betting. But I see little chance of a federal ban returning; the industry revenue and state tax revenue is far too high, and the sports leagues too dependent on it.

Casino table games are very hard to classify in this rubric. Some games have a very low House edge (like blackjack or craps), and can also vary tremendously in their social externalities; blackjack and craps are sometimes played in large, boisterous groups and seem culturally more like home poker games; other times they are solitary games that seem very depressing. Blackjack also involves a level of skill that makes it tough to categorize and, in theory, even involves an edge for the player if they are employing card counting strategies.

Two things:

1) A minor point, but a significant number of successful sports bettors aren't successful because they have their own models, it's because they are identifying market trends such as line movements on the sharpest books, and hitting stale lines on the duller "recreational" books that are slower to adjust, and beating CLV that way. These "top-down" bettors don't usually know *why* the lines are moving, but they see that they are, and that's good enough.

2) Gambling can be restricted without making it illegal. Indeed, all things considered, it may be best for sports betting to have a legal, state-regulated outlet. But there is another legal, extractive, and addictive industry that once could advertise on TV, and no longer can: smoking. If those rules can be changed for Philip Morris, they can be changed for FanDuel. Official marketing partnerships with the leagues should also be prohibited.

A friend, who was in recovery from addiction to alcohol, drugs and gambling, told me thst for a gambling addict the issue is not winning. It's not losing. He said that when he hit the jackpot, or a hand of poker, he never put the winnings in his pocket. He put them right back into the game, until he'd finally lost it all. I get the thing about adult consent, and don't know how to save addicts from themselves (except through 12 step programs), but it's time we recognized gambling addiction as being an illness, like alcohol addiction. That brings a different perspective on it, from the moral perspecive.